Woven Legends and the Rug Renaissance

Harald Bohmer, who launched a rug renaissance in the 1980s with the introduction of natural dyes to modern rugs, was a German student who studied in Turkey. He fell in love with the country, and his interest in rugs and dyes became a passion. When he learned of a method for analyzing the dyes in fabrics (thin-layer chromatography), he began a methodical investigation into the dyes in Turkish rugs. He learned what natural dyestuffs rugmakers had used 100 years earlier, before the dyer’s art had been lost, and how these artisans had used them.

Dr. Bohmer conceived the notion of teaching Turkish rug weavers the art of dyeing with natural substances. Eventually the School of Fine Arts in Istanbul agreed to sponsor a project with Dr. Bohmer as chief advisor, called DOBAG, an acronym in Turkish meaning Natural Dye Research and Development Project. Weavers in the villages around Ayvacik started weaving natural-dye rugs under Dr. Bohmer's supervision. DOBAG was the start of the Oriental rug renaissance.

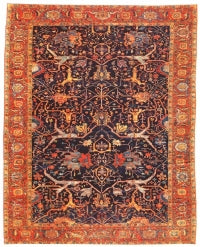

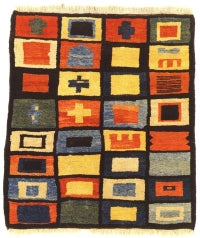

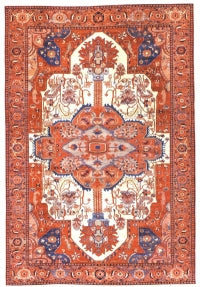

George Jevremovic and his company, Woven Legends. took that renaissance much further. He was impressed when he first saw DOBAG-inspired rugs from the villages around Ayvacik. In 1983 he began asking weavers around Ayvacik to make rugs for him, but he quickly realized that the nature of Ayvacik tribal and village life didn't allow him to make larger carpets. He wanted the same kind of charm and naivete in large rugs that one usually finds only in small ones, and he wanted to weave rugs in early tribal or village designs, especially designs from northern Iran. Up to that time, nearly every large rug, old or new, was curvilinear and formal-looking.

Between 1984 to 1987 George Jevremovic slowly established his Woven Legedns production of natural-dye rugs in Turkey. But the major obstacle was a lack of models for what he was trying to do. Everything had to be worked out. Although handspun wool was still available in Turkey, quantities fell far short of what he needed. He had to seek the advice of experts on natural dyeing. Eventually Woven Legends employed 15,000 people: spinners, weavers, dyers, and others.

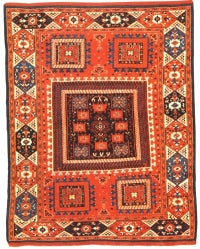

Turkish Bidjar (Euphrates line) from Woven Legends. It is based on a mid-19th century Persian Bidjar.

Woven Legends showed that antique designs could be beautifully rendered in new carpets. These are the first new rugs with true character to be seen in the west in a century. This was due in large part to the fact that weavers were allowed the freedom to improvise enough so that they were able to imbue their rugs with some of their individual spirit.

When George Jevremovic was asked which rugs he considered to be collectible, he replied ’some of the Turkish rugs’. He said he experiences the weavers in China and India as being agreeable, cooperative and skillful. He has a different experience when he asks Turkish weavers to weave rugs from drawings. They too are skillful and would like to please, but there is something -- he calls it "DNA" -- that makes them a little resistant to following someone else’s drawings! **

**Information for this article drawn from Oriental Rugs Today by Emmett Eiland.